|

Diphtheria is dangerous because the bacteria which cause it produce a powerful toxin (poison). The toxin kills cells in the mouth, nose and throat. The dead cells quickly build up and form a membrane which can attach to the throat and lead to death by choking. Diphtheria can also affect the heart (causing heart failure and death) and the nerves (causing neurological damage including weakness and numbness of limbs).

Three species of diphtheria bacteria produce toxins that are able to cause severe disease.

- Corynebacterium diphtheriae is the most infectious of these bacteria, and also the most common globally.

- Corynebacterium ulcerans is less common; it can cause classic diphtheria symptoms as well as a form of diphtheria that affects the skin and causes ulcers. This form of diphtheria usually occurs in countries where it is difficult to practise good hygiene.

- Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is also less common.

The last two species are often associated with farm animal contact and raw dairy products. Some strains of diphtheria bacteria do not produce toxins and cause only mild disease, such as a sore throat.

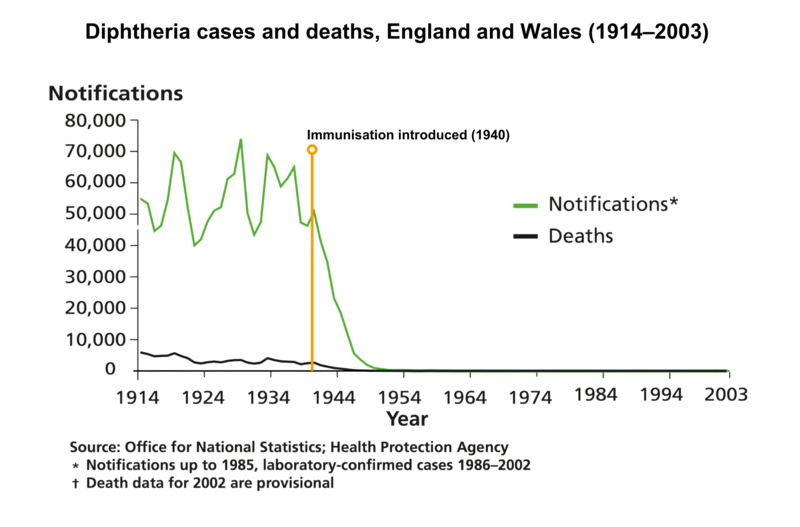

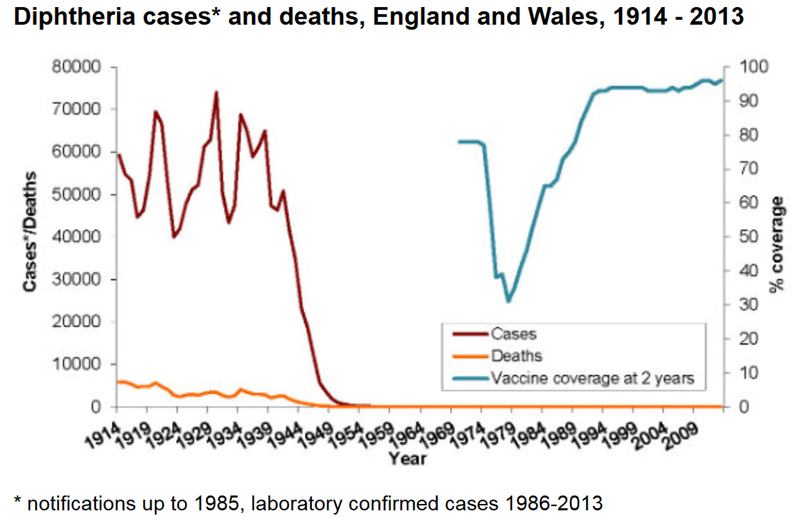

The graph below shows that before vaccination was introduced in the UK in 1942, there were on average 55,000 cases of diphtheria leading to around 3,500 deaths each year (mostly children). The vaccine has been so effective, diphtheria has caused only four deaths in the UK in the last twenty years. All of these people were unvaccinated. Most cases of diphtheria that have occurred in recent years in the UK have been brought in from the Indian subcontinent or from Africa.

The number of diphtheria cases in the UK is very low at the moment (10-20 confirmed cases a year over the last 20 years). However, because diphtheria is so infectious, there is a risk that an outbreak could occur if vaccination levels fall. An example of this was shown in the countries of the former Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The Soviet Union had a well-established programme of childhood vaccination. However, after it broke up into separate countries, childhood vaccination levels fell, and this led to a diphtheria epidemic.

Between 1990 and 1998 there were 157,000 cases of diphtheria and 5,000 deaths. The outbreak was eventually brought under control by a massive vaccination programme. See Diphtheria in the Former Soviet Union: Reemergence of a Pandemic Disease  for more information. for more information.

Click here for an accessible text version of this graph

Source: Public Health England

|